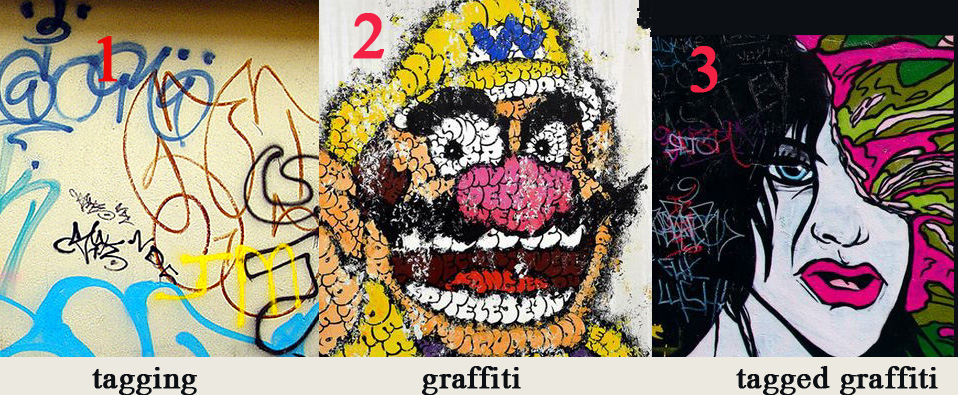

Unfortunately I did not have my 95% ethanol with me. After I transferred to another school, I still encountered the occasional tagging. Interestingly "graffiti" is rooted in the Italian word for "scratch". Tagging, technically, is less artsy than true graffiti.

While the former is used by street gangs to mark territory, most individuals' scratches and scribbles are merely an attempt to publicly declare individuality while they disregard others' property.

While the former is used by street gangs to mark territory, most individuals' scratches and scribbles are merely an attempt to publicly declare individuality while they disregard others' property. When that property is a metallic surface such as a locker, the ethanol wipes the ink away beautifully, without a trace. It's also effective on wood surfaces when the markings are fresh, but unfortunately absolute ethanol can also dissolve the varnish.

That's one of the challenges in removing graffiti. The most common medium, spray can paint, can host a variety of compounds: polyurethanes, lacquers and enamels. For each of these, there are solvents capable of forming intermolecular bonds with the compounds that are stronger than those between the latter and the background. Examples include butanone (MEK= methyl ethyl ketone) and xylene. But in attempting to remove graffiti, there's the risk of letting the paint penetrate deeper and of damaging the surface itself. It's advisable to begin by testing a solvent on small areas.

When cleaning masonry especially, the cleaning product is best applied to a poultice, a porous solid filled with solvent. This extends contact time between the cleaning fluid and the surface and prevents spreading of pigments to unaffected areas. Since water does not dissolve in organic solvents, the surface should be dry. In cases where the tagging is recent, an ammonia solution with a pH less than 13 also works and is safe on most surfaces. And since ammonia is water-soluble, the surface could be wet. Some granites and most sandstones, especially those of a green or grey color, are sensitive to alkaline solutions, so highly concentrated solutions of NaOH or KOH are not recommended. At the other pH-extreme, most acids are not only useless in attacking paints, but they will also dissolve and thus damage anything with carbonates: marble, limestone and terracotta.

If there are still residual pigments after treatment with a solvent, they can be bleached with swimming pool disinfectant: calcium hypochlorite, Ca(OCl)2. Since this compound is only slightly alkaline (it's the product of a weak acid and strong base), it's innocuous towards both acid-sensitive and alkali-sensitive surfaces. Most commercial products use a shotgun approach by blending several agents. For example, an old recipe uses a blend of Ca(OCl)2, pine oil and ammonia. Another employs base, ether, ethanol and a ketone. Concoctions, however, can sometimes be less than the sum of their parts, and the more meticulous approach is recommended for prized masonry. More recent patent-pending formulas are interesting from an environmental point of view because they use a combination of esters and surfactants.

Since solubility and evaporation rates are both temperature-dependent, an attempt to remove graffiti in extreme temperatures will render the cleaning operation less efficient.

Sometimes the desire to avoid harsh chemicals tempts one to use high-pressure washing or abrasives, but these damage masonry, at times even etching a permanent outline of the graffiti.

Sometimes the desire to avoid harsh chemicals tempts one to use high-pressure washing or abrasives, but these damage masonry, at times even etching a permanent outline of the graffiti. A better alternative to grinding, albeit expensive and tedious, is the use of lasers, which have come to the rescue of defaced historical artifacts. When an Nd:YVO4 (neodymium-doped yttrium orthovanadate) laser was used on various granites, the effectiveness was not affected by the type of rock, but it did vary with the composition of paint used, especially if it was reflective.

Sources:

Sasha Chapman. Laser technology for graffiti removal Journal of Cultural Heritage Volume 1, Supplement 1, 1 August 2000, Pages S75–S78

Martin E. Weaver. Removing Graffiti from Historic Masonry

http://www.usheritage.com/form/brief38.pdf

T. Rivas. Nd:YVO4 laser removal of graffiti from granite. Influence of paint and rock properties on cleaning efficacy Applied Surface Science Volume 263, 15 December 2012, Pages 563–572